European Digital Arts & the Lineage From Which the Concert ATOTAL is Derived

Franck Vigroux and Antoine Schmitt are a key pair of artists within France’s “pluri-” or “multi-” disciplinary field which rests at the intersections of noise and drone musics, digital arts, techno music, musique-concrète (sonic atmospheres), dark metal, and what late nineteenth / early twentieth century European opera composers, architects and choreographers called the Gesamtkunstwerk, or “total work of art”, whereby all of the arts and all of the senses were activated in order to produce what Richard Wagner, Friedrich Nietzsche and others argued was a balance between rational understandings of the art work (“Apollonian” forces) and an ecstatic, non-rational fusion with all of these elements and with the collective of other audience members experiencing them with you (the dangerous but enjoyable “Dionysian” aspects of human existence, which transcend social barriers of class and so on, to produce an ecstatic union).

Vigroux’s musical compositions vary from pummelling digital sounds which recall what pioneering German industrial music duo DAF called electronic “body music” (“körpermusik”), only much heavier in realization, and which have been likened to the work of Author and Punisher, Venetian Snares, and others (a good example is Vigroux’s collaboration with Finland’s Mika Vainia). Vigroux describes his work as an attempt to “regenerate music theatre or hybrid forms”, and he has staged a number of wonderfully bizarre, abstract and noisy theatrical works such as Flesh (2018), which might be best compared to the mind-bending performance-tableaux directed by Romeo Castellucci (scored in some cases by musique concrète artist Lilith, aka Scott Gibbons). Castellucci’ s epic productions wowed Australian audiences in the 2000s.

The precise manipulation of costume, objects, projection, lighting, hair, and body, which these audio-accompanied moving sculptures required meant they rarely toured Australia. While several of our extremely talented artists work in related fields, Australians are more restricted in terms of funding, logistics and institutional support. Australian sono-theatre of the image therefore has, out of necessity, embraced a reassuring messiness and sense of decay—consider for example Emma Fishwick in Perth, Aphids in Melbourne, and others.

Vigroux and Schmitt by contrast have initiated highly produced works with Paris’ Pompidou gallery (home to the IRCAM Institute of Research and Coordination of Acoustic Musics, established by stellar composer Pierre Boulez in 1970), Austria’s Ars Electronica (1979+), and Madrid’s Teatros de Canal festival, as well as Vigroux’ own label Cie d’Autres Cordes (Other Strings). With the demise of Australia’s Electrofringe in Newcastle after 2011, Perth’s BEAP following 2007, and last year’s brutal de-institutionalization of SymbioticA, Australia has no comparable digital arts networks today.

In Europe, though, the affiliations and links traversed by Vigroux and Schmitt are shared by the likes of noise guitarist Kasper Toeplitz, noise music empresario Phill Niblock, quiet listening / drone god Éliane Radigue, electro ensemble Zeitkratzer (all of whom Vigroux has worked alongside), as well as electro-acoustic opera devisor and videographer Wilfried Wendling (whose breathtaking work with famous French actor Denis Lavant I discuss here), dance-theatre director Aurélien Bory’s Plexus (which toured Perth 2016), and the elegantly mediative, sounding sculptures by Céleste Boursier-Mougenot (whose gorgeous works From Here to Ear, 2019, and Clinamen, 2013, toured Australia).

Videographer Antoine Schmitt—like Boursier-Mougenot—works predominantly in material sculptures, installation, and screen based art. Schmitt and Vigroux have collaborated on a number of closely synchronized audiovisual performances—notably Cascades (2022, which toured Melbourne in March 2023), the thunking K-rock road-trip Vidéoscope (2023), and the more dirge-y Chronostasis (2018).

Vigroux’s notes for Atotal positions the piece on the boundary of the known and the unknown, the chaotic and the governable, between structure and abject noisy mess. Vigroux’s commentary is almost as bombastic and pummelling as the influences he cites. Vigroux namechecks “Laplace’s demon” (a physics postulate that if someone—a “demon”—could know everything about the location, velocity, mass, and so on, of an object, one could perfectly determine in advance its future; a concept Einstein and chaos theory has firmly debunked), Gödel’s incompleteness theorem (which broadly states that, since mathematics is a symbolic system which refers to itself and the relationship between numbers, that it cannot ever prove for all cases that to which it refers), Lucretius’ “clinamen” (the Greek philosopher’s term for the unpredictable swerve of atoms which, by implication—since we are all made up of atoms—allows for the possibility of free will), as well as Heisenberg’s famous “uncertainty principle” (that we cannot know both the position and the velocity of a subatomic particle), and Schrödinger’s unfortunate cat (a metaphor explaining how the very measurement of something may bring about the conditions which we are attempting to identify).

Vigroux thereby suggests that by balancing order and disorder, chaos and digital determinism, Atotal constitutes a reflection on the totalitarian aesthetics of the likes of architect Albert Speer, whose 1934 Cathedral of Light consisted of a series of breath-taking illuminated columns “Designed to illuminate Nazi stadium rallies” such as the famous Nuremberg rally of the same year filmed by Leni Riefenstahl (Triumph of Will, 1935) and which were often accompanied by Wagner’s music. Speer’s work was cited by no less than Allan Kaprow—one of the key founders of anarchistic performance art—as a key precedent against which his own more playfully chaotic and hippie-ish events might be positioned (see Henri, Total Art, 1974).

The organising principal of fascist cultural production was to erode personal distinctiveness by engaging all of the bodily sensations so that one might experience a kind of joyful dissolution into Hitler’s, Speer’s and Goebbels’ model of “One people, one Reich, one Germany, one blood” through not only participation in the rallies themselves, but in other embodied actions and performances like “making new fields for the farmers … planting trees”, listening to the Fuehrer on the radio, athletics, and so on.

Drawing on the famous writings of Wagner and Nietzsche, electronic music composers have long recognised the conflicting possibilities of ecstatic liberation in the face of sensory assault (or, as one might phrase it more informally, “Freaking hell, that is so cool that I can forget everything, all my work stress, and just become one with the music and dancers in the room with me!”—the Saturday Night Live model, if you will) versus oppressive mind control (the massification of sensory overload to produce a group of stunned, willing participants to their own oppression, which Siegfried Kracauer and others saw in much mid-twentieth century mass art, fascist or otherwise). Howard Slater, Csaba Toth and others have argued that this is a foundational concept in post-industrial electronic music as a whole, where (in the terms of Ronald Bogue and Michelle Phillipov) “‘plotless’ song structures, combined with its high volume … and timbral” variations creates a “music of intensities, a continuum of sensations (percepts/affects) that converts the lived body into a dedifferentiated” mass, which might be considered (in terms) a “liberating, libidinal dissolution of the self and of the organism as an integrated system”. In other words, if mass society and industrialization is dehumanising, then why not embrace this and go beyond these experiences of dehumanisation to bond with other outcasts in the post-industrial wastelands of northern Britain’s cities, post-war Germany, the US rust belt, or for that matter the clubs of Perth.

ATOTAL: The Concert Itself

This is all pretty heady stuff if you trace its art-historical lineage, as I do above. So what, at least in the formulations of Vigroux and Schmitt, does it all add up to audiovisually?

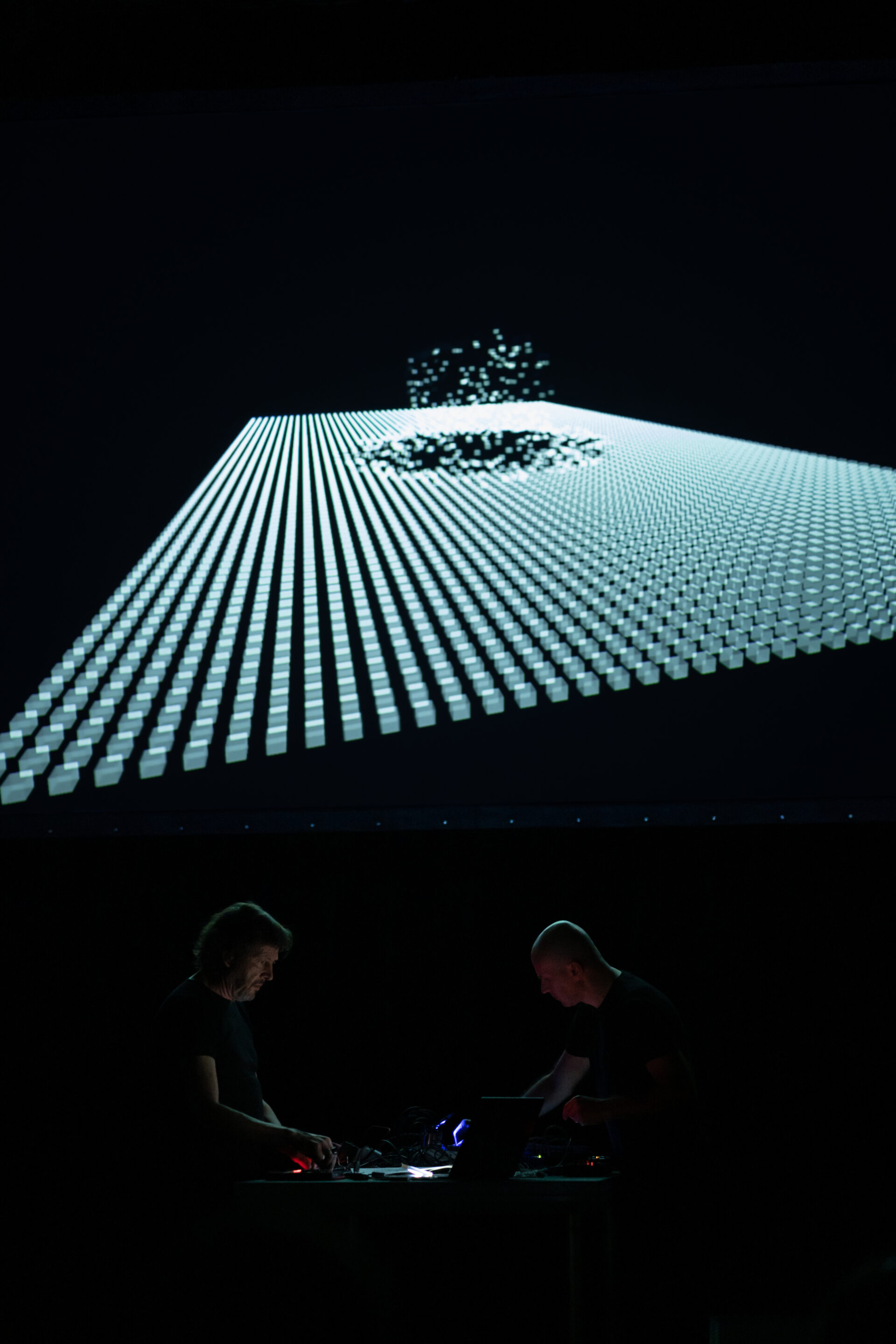

Well, basically there is a early signature sequence to which we return of fiercely banging beats and minimalist techno which later evolves into thunderous slamming noise—all accompanied by elegant, morphing projections elaborating on black-and-white grids, vanishing point perspectives, and the “squares” (actually cubes), “pixels” and “visual and audio atoms” which Schmitt sees his work as based upon. In between we are treated to some relatively dreamy, diffused noisy atmospheres with little direction or rhythm. As Paul Simpson argues, these extended breaks “seem necessary in order to provide contrast, but they’re definitely not as interesting”.

The key introductory and closing sections constitute therefore the most techno-industrial parts of the piece, structured around two distinctly sounding notes announced above a repeating deep bass tone. The vertical arrangement of these three signature notes (high, higher, and bass), along with the call and response arrangement of them, advertises the sonic architecture of the larger work, and the careful differentiation of frequencies and materials in the mix as a whole, as well as creating a sympathetic relationship between the central tones which are later obliterated by a density of material. The paired notes, initially foregrounded and later dropped behind the ominously louder bass tone, are echoed by the monochromatic dualism of Schmitt’s projections, which are in turn focused around the contrast between the extremely bright projection of almost pure black, versus blinding whites—with almost no grey or colour. Schmitt’s visual accompaniments therefore recall most closely those of Japanese digital legend Ryoji Ikeda in the uncompromising use of purist geometric and/or particulate black and white elements rushing at the viewer—although one might also consider the work of Pan Sonic, UK duo Demdike Stare’s collaborations with audiovisual artists like Michael England (Dark Mofo 2019), and other reference points.

The intervening, sometimes airy but harsh atmospheres are, well, less compelling, but are held together by the promise of the return of the beat, which is deferred but implied over a long period. Throughout this, Schmitt’s field is displayed as a planar assemblage of white blocks which rotate, twist and bubble upwards according to various perspectives. For me at least, the onslaught of cubes was most compelling when either laid flat as a one dimensional grid across the screen (recalling both Ikeda and one of the major trends identified by Rosalind Krauss of post World War Two art in the focus on “the grid” as a powerful but depersonalising motif in and of itself). Schmitt also offers a visual representation of Kraucauer’s theory of flatness and simultaneity, where the Star-Trek-like rush of almost warp speed objects promises a final realisation in which all of the lines, points, cubes, rectangles and pixels hurtling about the centre of the screen will coalesce into a kind of everywhere everywhen at once, squashed into an absolute unifying simultaneity.

It’s all pretty mesmerising stuff. Whether it lives up to the socio-political critique implied by Vigroux is a moot point, but as an at times punishingly forceful set of beats and atmospheres in sync with an enjoyably overwhelming, super-bright light show, Atotal is fantastic—very much on the Dionysian side of art. One can only hope that some of the more embodied and overtly performative versions of Vigroux’s experiments in mise en scène make it to Australia in the future, of which Atotal provided but a taster.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ATOTAL

Audio-visual concert, devised and premiered in 2021.

Franck Vigroux: Live digital music

Antoine Schmitt: Live generative video projection

Presented by Tura in Perth 2023

Franck Vigroux’s and Antoine Schmitt’s National Australian tour has been made possible through the support of French Institute Paris, Embassy of France in Australia, CNM and Occitanie en Scène. Cie d’Autres Cordes is supported by the Regional Council and DRAC Occitanie France.

Assoc. Prof. Jonathan W. Marshall has published arts criticism in Perth, Melbourne & Aotearoa New Zealand for over 20 years; he is the coordinator of postgraduate studies at the Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts, Edith Cowan University.